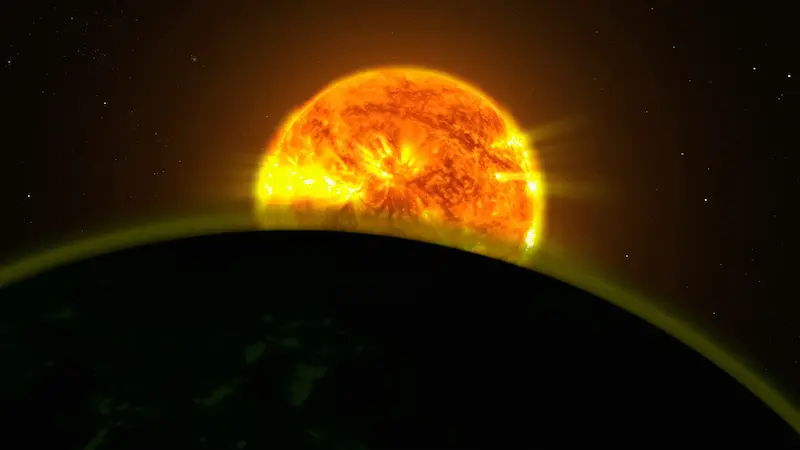

If you’ve been following the current AI race, you’ve probably noticed the pattern: every leap in models and capabilities comes with a massive electricity bill… and a big water bill too. That’s why several US tech companies are pushing hard for an idea that sounds like science fiction, but is starting to become real (or rather, to reach orbit): building data centers in space. The pitch is as straightforward as it is ambitious: put servers on satellites, power them with near-constant solar energy, and use the vacuum of space to deal with heat without relying on water-based cooling systems.

At its core, the goal is clear: if AI infrastructure on Earth is straining power grids and local resources, why not move some of that compute into orbit, where photovoltaic generation can be far more efficient and cooling doesn’t demand gallons upon gallons of water? The answer isn’t a definitive “yes” yet, but the signals are adding up: Google already has a timeline, NVIDIA has already put hardware into orbit, and SpaceX, OpenAI, and other major names in the sector have shown interest.

What a space data center is—and why it matters now

When people talk about “data centers in space,” they don’t mean a single gigantic satellite acting as a floating server. The concept is more modular: deploying groups of satellites with computing and communications capabilities that operate as processing and storage infrastructure in low Earth orbit. The idea is to replace—at least in part—the runaway growth of terrestrial data centers, especially for AI-related workloads.

The main technical argument revolves around energy and cooling. In orbit, electricity can be generated with photovoltaic cells almost continuously, and Google has indicated that solar generation efficiency could be up to eight times higher than what you get on Earth. On top of that, waste heat can be dissipated into space, removing the need for huge volumes of water for cooling—a sensitive issue in many regions where data center demand is already pushing water resources to the limit.

The backdrop driving this search for alternatives is projected consumption. BloombergNEF estimates that US data center electricity demand will reach 106 GWh in 2035, a scale comparable to more than 100 large nuclear power plants. That figure was revised upward by 36% versus a forecast from just seven months earlier, and it’s roughly 2.6 times the demand projected for 2025. With that outlook, it’s no surprise local resistance to new facilities is growing—along with concerns about energy prices and planning.

And that leads to the inevitable rhetorical question for any tech-leaning reader: if AI is set to grow at full throttle, are we really going to keep trying to plug it all into the same Earth-bound socket?

Google, NVIDIA, and Starcloud: the first real steps

On this board, Google (Alphabet) has already put a name and date on its move: Project Suncatcher. As announced, the company plans to launch two experimental satellites in early 2027, equipped with its high-performance AI semiconductors, TPUs. The approach is to scale through multiple small satellites that combine solar panels and compute capacity, working together as a distributed data center in orbit.

What gives the concept even more credibility is that it’s not just a plan: an NVIDIA-backed startup, Starcloud, has already moved first in the field. The company took the AI semiconductor NVIDIA H100 into space in October, and its first satellite, according to NVIDIA, weighs 60 kilograms and is roughly the size of a small fridge. The key here isn’t just miniaturization—it’s the industrial signal: AI hardware is already operating beyond the atmosphere.

What’s more, reports say the system continued to be used and enabled continuous AI model execution. In parallel, Starcloud also demonstrated a symbolic milestone: training a small-scale AI model in space, using Google’s Gemma model on a satellite. It’s an early step, but it’s exactly the kind of test that turns a futuristic idea into a roadmap with measurable milestones.

Following the same logic, Starcloud is already looking to the next phase: it plans to launch a larger satellite with a GPU cluster toward the end of 2026, and aims to offer space-based computing services in early 2027. In an industry that often runs on promises, these timelines stand out—even if we’re still in the experimental stage.

SpaceX and OpenAI: huge opportunities, equally huge barriers

If there’s a company that fits almost “too perfectly” into this story, it’s SpaceX, for an obvious reason: it controls rockets, satellites, and launch costs within the same ecosystem. In this context, it has been suggested that SpaceX is preparing a possible IPO in 2026, and that part of the funding could go toward space-based AI data centers. Elon Musk has even said the idea is good, and has gone as far as suggesting that space could become the cheapest place to train AI within about five years—a provocative claim, but one that targets the heart of the problem: the energy and infrastructure cost on Earth.

OpenAI is also on the radar. Its CEO, Sam Altman, has previously said that building data centers on Earth “may not make sense,” and interest has been reported in space data center options, including moves to get closer to startups in the rocket sector. Meanwhile, spending on terrestrial infrastructure keeps climbing: OpenAI is said to be planning to invest $1.4 trillion in data centers over the next eight years, and Microsoft is expected to spend $80 billion in fiscal year 2025, with Meta and Amazon also investing heavily. The result: power grids and water systems under pressure, especially in the United States.

That said, the big “but” for space data centers remains the same: orbital costs and physical risks. Google has analyzed that if the cost of launch to low Earth orbit dropped to $200 per kilogram by the mid-2030s, the project would be close to viable, while consulting firms such as McKinsey put today’s cost around $1,500 per kilogram, and other estimates place it closer to $2,000 per kilogram. In other words, the economics hinge on the price of getting “metal” into orbit falling dramatically.

On top of that are serious technical constraints. Radiation accelerates aging and increases failure rates in electronics—critical when you’re talking about high-performance hardware. There’s also the risk of collisions with space debris, a problem that’s no longer hypothetical: one cited example involves a Chinese spacecraft that suffered window damage from a small fragment, a reminder that orbit is becoming an increasingly congested environment. And while the vacuum allows heat to be shed without water, thermal management for chips in space is still widely seen as a challenge that isn’t fully solved.

So for now, the space data center is a promise backed by real prototypes and major patrons—but also a field still grappling with physics, cost per kilogram, and the fragility of electronics outside atmospheric protection. What’s interesting is that with AI demand revving like an engine at redline, the industry is starting to take seriously options that just a few years ago would have belonged only in a science-fiction script… or an endless forum thread that never quite ends.